- Intercitrus has already described the South African decision to suspend orange exports from areas declared with this disease since September 15th as a “cosmetic operation” Given the data from October, is the fungus also present in supposedly free areas, or simply, their operators are not complying with their own regulations?

- With data up to October, the southern country has broken its own record and has already accumulated 51 interceptions in this campaign due to this disease, which consolidates an “unacceptable” annual average of over 40. The interprofessional demands, given the confirmed chaos in controlling this fungus, that in the next campaign the EU unilaterally suspend exports after the fifth rejection.

- Intercitrus reminds the European Commission that South Africa also fails to comply with the mandatory cold treatment in oranges to prevent the ‘False Codling Moth’ and that it is necessary to extend it to mandarins and grapefruits because they are also hosts of the pest and it is being detected in imported batches.

Intercitrus warned the European Commission (EC) in a letter on October 3rd that South Africa was on track to reach “record interception figures” in European ports for citrus affected by pests or diseases whose control is regulated as ‘priority’ by the EU, such as the ‘Black Spot’ (CBS). Indeed, pending the counting of November, official data from the Europhyt-Traces portal confirms this, revealing that up to October, 51 South African shipments affected by this fungus were detected, marking the highest number in its history. Furthermore, of the 13 rejections recorded in the last month, 12 occurred in oranges, theoretically impossible since, according to the decision taken by exporters in this country and accepted by their authorities, only oranges produced in South African areas declared ‘exempt’ from this disease could be sent to the EU from September 15th onwards. Intercitrus, which has already described this measure as a “purely cosmetic operation,” confirms the “lack of credibility” of South African authorities in plant health matters: either their operators have violated the regulations they imposed on themselves and continued to send oranges from areas declared with the disease (those in the Eastern Cape), or the ‘Cirtus Black Spot’ is also widespread in areas officially recognized as exempt. This is pointed out by the president of the interprofessional, Inmaculada Sanfeliu, who demands that for the next campaign, “given the proven chaos over the last three years in controlling this disease, the EC imposes automatic closure of South African citrus imports after the fifth rejection.”

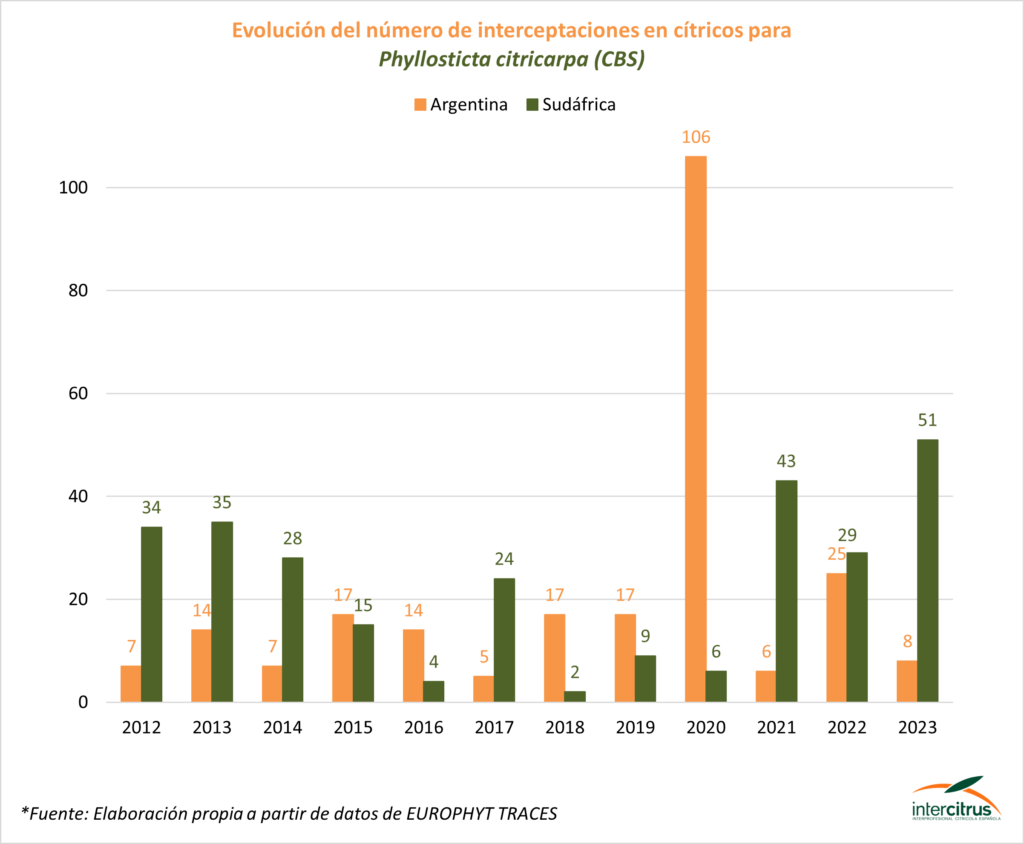

South Africa’s problems with CBS control, as seen in the attached graph, are not temporary. In the last three campaigns, the consolidated annual average at the end of the southern hemisphere import season already exceeds 40 rejections for this reason. This amount far exceeds the worst average records accumulated by this country between 2012 and 2014, which prompted the EU executive to unilaterally suspend imports from that country in that last year (although it did so symbolically in November of that year when its shipping season had already ended). At that time, in one of the considerations of the specific EU regulation to regulate import conditions related to this disease, the Commission itself proposed that it would act by automatically suspending imports after the fifth interception. Although this criterion was ultimately withdrawn, Intercitrus insists on reintroducing it now.

In April 2022, the Commission strengthened control measures on imports from countries with CBS problems, such as South Africa; in September of the same year, DG SANTE officials travelled to that country for an on-site audit, where some significant anomalies were detected that South African authorities committed to rectify; in September of this year – for the seventh time in the last 11 years – another announcement was made regarding the unilateral suspension of shipments from areas declared with ‘Black Spot’, which has now been shown – as had happened in previous years – to be completely ineffective. Nothing has worked to halt the threat of this pest, a fungus that is accredited to adapt to the Mediterranean climate and causes such blemishes on citrus skin that renders them unfit for fresh marketing. Furthermore, South Africa – far from correcting its deficiencies – has threatened to take the EU to the World Trade Organization (WTO), as it has already done in the case of the ‘False Codling Moth’. “Nothing works with the South Africans. If the EU wants to take plant health seriously, it must assert itself and impose an objective criterion, such as halting imports after the fifth rejection,” concludes Sanfeliu.

The situation with two other pathogens whose combat and surveillance are also regulated as ‘priority’ by the EU – which due to their greater economic, environmental, and social impact are among the top 20 most serious pests and diseases – is no less worrying, as Intercitrus already highlighted in the aforementioned letter of October 3rd. On one hand, the interprofessional conveyed South Africa’s non-compliance with the conditions regulated in 2022 for subjecting oranges from countries affected by the ‘False Codling Moth’ to cold treatment and therefore demanded and proposed specific measures to systematically verify their compliance in each shipment. In addition to this, confirmed detections for this same pest in tangerines and grapefruits from South Africa (3) and Israel (1) this year, according to the interprofessional, would justify the need to extend the cold treatment to all species that, like those mentioned, are accredited as hosts of larvae of this insect. On the other hand, emphasis was placed on the “alarming news of the detection of the Diaphorina Citri insect in Cyprus, in EU territory, as it is the most dangerous transmitting vector of the HLB, because it transmits the Asian variant (considered the most devastating citrus disease and for which there is no known cure), it adapts better to the Mediterranean climate (due to its tolerance to a wider range of temperatures than other transmitting vectors such as Trioza Erytreae), it is more difficult to detect, and it develops very favourably in the Citrange carrizo citrus rootstock, which is mostly used in the Mediterranean.”